The Hutton Lancaster Legacy Quilt, 1846-1847

Collection of Mary Holton Robare.

Photograph by Kay Butler.

It has been awhile since a post was made to this blog site, but my interest in historical quilts and the people who made them is still strong. Today's post will introduce you to the Hutton Lancaster Legacy Quilt, a Signature Album Quilt dated 1846-1847. I am thrilled that Kay Butler and Kelly Kout made a (now sold-out) kit of its block patterns and I recently had the pleasure of presenting a lecture to one of the groups to which they belong, the Heartland Quilters of the Eastern Shore. With many people now making their own versions of this old quilt, and fresh research being conducted, I hope you will enjoy learning about the original inspiration for some of today's quilters.

I initially purchased the Hutton Lancaster Lagacy Quilt due to its so-called "Apple Pie Ridge Star" block pattern. You can see this in the top row, third from the left. I have studied this pattern for many years and as former readers of this blog are aware, it is also known by many different names. You can read more about that here: January 19, 2019 post

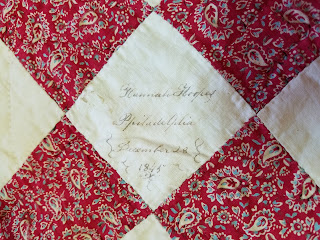

The overall dimensions of the Hutton Lancaster Legacy Quilt are 100 X 104 inches. It has thirty-six blocks measuring 12.75 X 12.75 inches. The width of its border is approximately 12 inches wide. Its binding was done by rolling the backing fabric to the front and it is quilted with wreaths, tulips and outline quilting. It has numerous, still-decipherable inscribed names, and is dated 1846 and June 17, 1847. There is one stamped inscription; the rest are written by various hands, in ink.

Hutton's Lancaster Legacy Quilt, detail.

Block inscribed, "Elizabeth Gregg, June 17, 1847.

When I bought it, the only information concerning this quilt's history was that it was previously owned by a resident of Kentucky, USA, who was a descendant of the maker. She reported that, "Grandma's quilt had been found in a trunk accompanied by a newspaper from Cambridge, England," and that it was wrapped up in a package with a strand of red hair. I have yet to find any connection to Cambridge and I wish we could have conducted DNA analysis on that long-lost strand of hair! Nonetheless, due to the quilt's many signatures and dates, and with research assistance from Glorian Sipman, we were able to learn a great deal more about it. We even found a "Quaker Connection."

At least nine of the names on the quilt represent members of the Benjamin and Susannah Miller Hutton family. They, and almost all of the other signatories, were residents of Drumore and Peach Bottom, which are now both part of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

In 1816, Benjamin, who was a farmer, married Susannah Miller 'out-of-meeting.' Although this usually resulted in disownment, according to minutes of the Little Britain Monthly Meeting the committee assigned to Benjamin recorded that his "disposition was favourable." On the 11th month 9th day of 1816, Benjamin acknowledged, "[...] being educated among Friends, have so far deviated from their established order, as to keep company with and marry a Woman not in membership, by the assistance of a Baptist teacher, [...] desiring Friends to continue me under their care, hoping in future my conduct may render me worthy of such indulgence." The Meeting agreed to retain his membership until 1835, when he was removed for non-attendance, but after the first four of his and Susannah's nine children were born.

Page from a book of minutes from the Little Britain Monthly Meeting

showing dealings with Benjamin Hutton.

Some of the other identities of the quilt's inscribed names were also found in records of the Religious Society of Friends. Others were affiliated with Presbyterians and Methodist Episcopalians.

Hutton Lancaster Legacy Quilt, detail.

Block inscription interpreted as, "Nancy A. McCullough, June 17, 1847."

I plan to share more about this quilt in future posts. In the meantime, during whatever holidays you celebrate this year I wish all of you the best, with hopes for happy, peaceful days ahead.

.jpeg)

.jpg)